Dara Lind explains the child migrant crisis in two minutes.

The flow of unaccompanied immigrant children across the US-Mexico border — mostly from Central America — is continuing to gain attention as a humanitarian crisis.

So here are 14 things you need to know to get a handle on what is actually going on along the border right now; what process the US has in place to deal with unaccompanied kids and families; and what the government wants to do now.

(For more on this story, see Vox's cardstack and storystream on the crisis.)

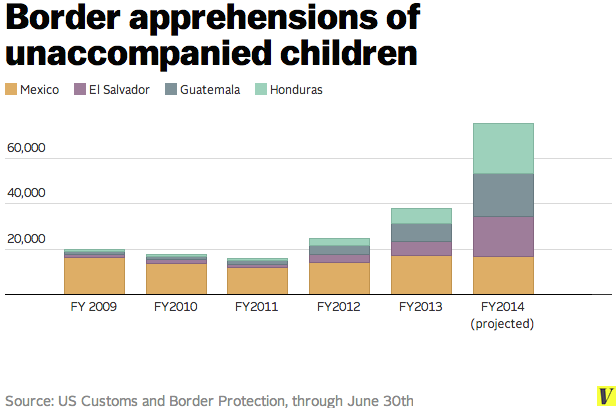

1) The child-migrant "surge" began in 2011, but hit a crisis point this year

Border Patrol agents began reporting an increase in the number of unaccompanied children from Central America in the fall of 2011. Because fiscal year 2012 started in October 2011, the government's official numbers show an increase starting then — but anecdotal reports demonstrate that the surge began early that fiscal year, i.e. in 2011.

But this year, the surge has accelerated. In fiscal year 2014, an estimated 77,200 children are expected to get apprehended at the border — including 59,000 children from Central America.

US Customs and Border Protection says that apprehensions of "unaccompanied alien children" (the official government term) are up 106 percent from this time last year.

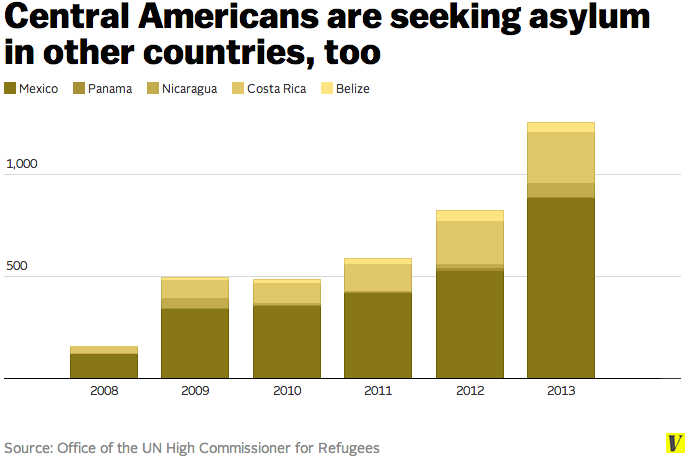

2) The current crisis stems from the fact that more children are going from Central America to other countries throughout the region

In fiscal year 2014, for the first time ever, the majority of unaccompanied children are coming from Central American countries. In fact, fewer children are coming from Mexico than from Guatemala, Honduras, or El Salvador.

Gang violence in Central America, especially in Honduras and El Salvador, is driving a substantial exodus to other countries throughout the region. In particular, teenagers in these countries are being recruited to join gangs; if they refuse, the gang will often retaliate against them and their families.

While the United States is receiving many of the children and families fleeing Central America, other nearby countries are also seeing a rapid increase in the number of Central Americans seeking asylum. Even Nicaragua, which is one of the poorest countries on earth, is receiving asylum seekers from Central America.

For a closer look at why children and families might be coming, see here.

3) Some of the children who are coming have parents in the US; some of them don't

The current influx isn't just about parents "sending" their children on a life-threatening journey to the US — or about children coming to reunite with their parents who are here as unauthorized immigrants. Some of the children arriving do have parents or relatives here; many do not.

A UN Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees study published this spring found that 36 percent of the unaccompanied immigrant children it interviewed had at least one parent in the United States. (Not all of those children, however, said that reuniting with family was one of the reasons they'd come from their home countries.) So for some of these children, being reunited with family would mean being sent back to their home countries; for others, it would mean staying in the United States.

4) Mexican children can just be turned back at the border — and many want to start turning back Central American children, too

Not every child who gets apprehended at the border ends up getting taken into government custody.

Mexican children who are apprehended coming into the United States are interviewed by a Border Patrol agent very quickly. If the child persuades the Border Patrol agent that he or she is afraid of being persecuted or trafficked if sent back, then the child is kept in custody. But if the child can't pass the interview, he or she is immediately "returned" to Mexico.

Most child migrants have historically come from Mexico, and very few of them pass their screening interviews. This means that historically, the United States hasn't had to house too many child migrants. Now, with more children coming from Central America — who are automatically put into custody and given full court proceedings — the US has to house a much larger share of the children who cross.

The Obama administration and Republicans in Congress have both embraced the idea of changing the law, to children who are coming over from Central America the same way as children coming from Mexico: they'd have to pass an immediate screening interview in order to stay in the country.

That's likely to greatly reduce the number of children who are able to stay. But the rushed process is ending up sending Mexican children back into danger. That should raise red flags for any proposals to deal with Central American children the same way.

A Border Patrol agent and child in Texas. Via Customs and Border Protection on Flickr

5) Congress set the rules on dealing with child migrants under the Bush administration

The Obama administration doesn't have much leeway in dealing with unaccompanied child migrants. That's because Congress set a particular process here as a way of fighting human trafficking.

Most of this process was codified by Congress under the Homeland Security Act of 2002; Congress added some additional protections under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, in 2008.

Under current law, the Border Patrol is required to take child migrants who aren't from Mexico into custody, screen them, and transfer them to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (a part of the Department of Health and Human Services).

The law tasks HHS with either finding a suitable relative to whom the child can be released, or putting the child in long-term foster care. For more about how that process is supposed to work — and some of the problems with it being overloaded — see here.

The inflexibility here is one reason why the Obama administration and Congress are now talking about changes to the law.

Children being escorted to make phone calls in a temporary Border Patrol holding center. Ross D. Franklin/Getty

6) Border Patrol is under the most strain in dealing with child migrants

No part of the federal government is well-equipped to handle the current influx. But since Border Patrol is the first government agency to come into contact with immigrant children, it's bearing the brunt of the overload.

The laws passed by Congress under the Bush administration put Border Patrol agents in charge of screening immigrant children, and holding them for up to 72 hours before they are transferred to HHS. But Federal Emergency Management Agency director Craig Fugate has admitted that the government has had to exceed the 72-hour limit in most cases. Many children are being housed in Border Patrol processing centers — essentially prisons — or in makeshift facilities in military bases.

Border Patrol agents and experts agree that Border Patrol agents shouldn't have so much responsibility for dealing with child migrants. Agents say that Border Patrol's job isn't to deal with immigrant children, but rather to catch criminals crossing the border.

Advocates, meanwhile, believe that screening traumatized children who've just come over the border is very difficult, and something that should be done by child welfare experts, not by Border Patrol agents.

The Obama administration has asked for $68 million in increased border security, and $364 million for Border Patrol to screen and house children. But changing the law, as Congress is expected to do, would actually give Border Patrol agents more work to do, by giving them a bigger role in determining whether children should be sent back.

Children sleep on cots in the temporary processing center in Nogales. Ross D. Franklin/Getty

7) The agency responsible for long-term care is dealing with over six times as many children as they have beds for

According to Wendy Young of Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), an advocacy organization for unaccompanied immigrant children, the current system Congress put in place "was designed for about 6,000 to 8,000 kids a year — not the numbers we're seeing now."

That's borne out by this chart from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which compares the number of immigrant children Border Patrol is sending into HHS custody to the number of available beds in HHS facilities:

via www.hhs.gov

The administration has asked for $1.8 billion from Congress for HHS to provide long-term housing for children.

8) The government uses immigration court to figure out which children are eligible to stay and which aren't

One of the administration's top three deportation "priorities" is people apprehended by Border Patrol agents within 100 miles of the border — no matter what age they are.

In practice, what that means is that any adult, even an adult with children, apprehended by Border Patrol within the border area (unless they qualify for a special process called expedited removal) is put in criminal court to face charges of illegal entry or illegal reentry, or put in immigration court for deportation proceedings.

Under existing law — which has been in place for decades — the process is slightly different for immigrant children from Central America. If a Border Patrol agent thinks the child might qualify for asylum in the US, the child is interviewed by an asylum officer first — then, if the asylum claim is rejected, the child is sent into immigration court. There, a judge determines whether an immigrant can legitimately apply for legal status, or whether he or she should be deported.

Deportation proceedings can actually be an opportunity for immigrant children who qualify for some form of humanitarian relief — like asylum or Special Immigrant Juvenile Status — to get it. If they weren't put in deportation proceedings, in some cases, they'd just remain in the United States as unauthorized immigrants.

But immigration courts are severely backlogged. It takes a little over 19 months, on average, for an immigrant's case to be resolved. And many courts take longer. So even a child who will ultimately get deported might be able to stay in the US for a year or two before that happens.

The changes to the law that Congress and the administration are considering, however, would mean that children would only make it to immigration court if they passed their preliminary screening by a Border Patrol agent.

9) At least half of Central American child migrants should qualify for some form of humanitarian legal status

Under existing immigration law, if immigrants establish they were persecuted in their home countries, they are eligible to receive humanitarian status. This article takes a closer look at what the children and families coming from Central America might be eligible for.

A recent report from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees says that about 60 percent of children coming over from Central America might be eligible for some kind of humanitarian protection, according to international standards. (US standards are different.) And a Vera Institute of Justice report from 2012 identified 40 percent of immigrant children as eligible for some sort of legal protection under US immigration law. But the Vera report is based on numbers from 2010 — predating the current surge — so it's extremely difficult to tell whether it's representative of the immigrants crossing today.

A Guatemalan family crossing the border from Mexico. Omar Torres/AFP/Getty

10) About half of all kids are ultimately allowed to stay — but very few of them are physically being deported

Current government numbers show that nearly 65 percent of unaccompanied children who apply for asylum receive it. But very few unaccompanied children are actually applying. Through the first nine months of fiscal year 2014, only 108 unaccompanied children have been granted asylum. And as of March, only 1100 children were waiting for their asylum applications to be processed.

The rest of the children are going into immigration court, to determine whether they qualify for some sort of legal status. Some Republicans have alleged that most children never show up for their immigration court hearings. In fact, about 60 to 70 percent of Central American children are showing up for their hearings — closer to 70 percent of Honduran and Salvadoran children. It's not clear how many of the children who didn't show up to court were deliberately absconding, and how many simply didn't understand the process because they didn't have a lawyer.

Over the last decade, a little over half of all children in immigration court (not all of whom came into the US unaccompanied) have ended up getting a "removal order" — a formal order of deportation. A little over a quarter have been allowed to stay, either because the judge gives them legal status or because the judge closes the case while they pursue legal status another way. And the rest are given "voluntary departure" — they have to leave the country, but they don't face the lasting legal consequences of a deportation.

Here's what's happened to children whose cases have been filed since 2005:

Obviously, most children who arrived more recently — in 2013 and especially 2014 — are still working their way through the court process. Children whose cases were filed under the Bush Administration are pretty likely to have been forced to leave the country one way or another. (Some of those rulings, of course, happened under the Obama administration, years after the case had been filed.) Children whose cases were filed since 2009, and have already gotten a decision from the judge, are more likely to have been allowed to stay.

That's evidence that children who've arrived in the last few years, during the current surge from Central America, are more likely to qualify for humanitarian relief. (It's possible, though not likely, that judges are simply being more lenient.) But that trend might be misleading. It's possible that the kids still waiting for their cases to get resolved are more likely to get deported than the ones whose cases got resolved quickly.

About half of all children who get rulings from the judge are still getting ordered deported, even in recent years. But very few of them are physically deported by the government. Data appears to show that around 1,400 children were deported back to Central America in fiscal year 2013.

It's not clear whether the rest of these children "self-deported"; whether they absconded; or whether they simply didn't understand the system well enough, and fell through the cracks.

Boys awaiting medical screenings at the Nogales processing center. Ross D. Franklin/Getty

11) There's an additional crisis of families coming over into Texas

Complicating the debate over child migrants in particular is a surge of migrants of all ages, many of them single parents, from Mexico and Central America. Many of these migrants are also crossing into the United States in Texas — the same Border Patrol sector that unaccompanied children are crossing into. There aren't good estimates of how many of these families would be eligible for humanitarian relief.

There aren't as many legal protections in place for Central American families as there are for unaccompanied Central American children: families aren't automatically screened by an asylum officer, and can have their deportations expedited instead of going in front of an immigration judge.

Children in a holding cell at the Nogales processing center. Ross D. Franklin/Getty

12) For now, the government is detaining families en masse while they wait for their hearings

Most families are being put into deportation proceedings in immigration court. But immigration courts around the country are dealing with case backlogs that are months or years long.

Until recently, families apprehended crossing the border were simply issued a "Notice to Appear" in immigration court on a particular date — which officially starts deportation proceedings. Then, they were simply released. But n June 20, the federal government announced that it would stop releasing families after putting them into formal deportation proceedings.

The government is now hurrying to open detention centers for hundreds of migrant families, including a 700-bed facility in New Mexico. It's also expanding the use of "alternatives to detention," including ankle monitoring, for families that it doesn't physically detain.

13) The Obama administration's goal is to speed up deportations by making the existing process go faster

Because the process for dealing with child migrants is set down by law, it's not possible for the administration to implement a faster deportation process without changing the law. That's why the administration is considering asking Congress to change it themselves. (Some Republicans have suggested that the administration simply ignore existing law so that it can quickly deport all child migrants via "expedited removal" instead of putting them in front of an immigration judge, but the administration is clearly interested in changing the law rather than breaking it.)

A young boy in the Nogales processing center. Ross D. Franklin/Getty

But the administration's broader plan is to deport children and families who are already here more quickly by staffing up the immigration court system. It's announced surges of immigration judges and court staff to deal with children, and with Central American adults who were apprehended alone. Once it's opened family detention centers, it will send another court surge to process cases in those detention centers.

It's also changing the way that immigration court hearings are scheduled: now, judges are instructed to hear the cases of children and families who've recently come into the US before they hear the cases of other immigrants. (That will make the wait even longer for those immigrants whose cases get bumped.)

It typically takes months or years to get a hearing in immigration court. The administration's goal is to get through a case in a matter of days. One Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) official told the press that the goal of the detention center opening in New Mexico is to deport a family within ten or fifteen days. Only a few weeks after that announcement, the government started deporting the "first wave" of families from New Mexico to Honduras.

But immigration court hearings are also supposed to give immigrants the chance to establish that they're eligible for legal status. With the emphasis on deporting families and children quickly, it's not clear that they'll get the time, resources, or information they need to present a successful case — even if they do actually meet the standards for humanitarian relief.

14) It's not clear that the crisis can be resolved through "deterrence"

Much of the debate over the child-migrant crisis in Washington has focused on what to do to stop children and families from coming in the future. Whenever Jeh Johnson, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, has spoken about the child-migrant crisis, he's tried to speak directly to parents in Central America and tell them that their children won't be safe crossing into the US.

Even when politicians do make proposals to deal with children who are already here, they tend to focus on sending a message to families that might want to send their children in future — by making a punitive example of the children who are here now.

Many Republicans are calling for swift deportation of the children who are already here to send a message to others. And some Democrats who support comprehensive immigration reform have said that only a comprehensive bill will fix the child-migrant crisis in the long run.

Even the basic logistics of what to do with children who have already arrived and are in government custody are being seen through the lens of deterrence.

On July 8th, President Obama asked Congress for $3.7 billion: most of that money would actually go to deal with children who are already here, but it's being painted as a request for more money for border enforcement, to deter children from coming in future. And the proposed change to existing law, to make it easier to deport Central American children immediately, is being encouraged because sending children back would send a message to those who might arrive.

But there's no empirical evidence that this sort of deterrence would immediately stop children from coming — or that it would stop them at all. That's especially true for children who are fleeing violence, who are coming to the US because they have nowhere else to go.

The benefit is hypothetical. But the children who are already in the care of the US government and the families currently waiting for court hearings — and those coming in the immediate future — are real. And so is the danger that many of them are fleeing.

With the government poised to take a punitive, enforcement-based response, they're in danger of being merely collateral damage.